Loincloths, Muscles, Sorcery and the Rock of Uranus: A Journey Into the Realm of the Italian Peplum (c.1958-1965)

This article was written exclusively for The Film Magazine by Paul A J Lewis of paul-a-j-lewis.com.

‘Or if you want something visual that’s not too abysmal’, Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry) sings to Brad and Janet in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), ‘We could take in an old Steve Reeves movie’. With this, Frank-N-Furter references the ‘beefcake’ spectacle of bodybuilder-cum-actor Steve Reeves’ appearances in numerous Italian sword-and-sandal films, or pepla, of the 1950s and 1960s as an index of high camp – a subgenre of films predicated on the objectification of the muscle-bound male body.

The Italian peplum takes its name from the Greek word for ‘tunic’ and, though a retrospective label originally applied somewhat mockingly to the films by French critics during the 1960s, highlights the extent to which the Italian sword-and-sandal pictures of the 1950s and 1960s foregrounded a sense of visual spectacle and the combined texture of historical clothing, sets, bodies (male and female) in action – all given a sense of scale, regardless of how ludicrous the plotting (or the English dubbing in the export versions) was, via then-new widescreen processes. In other words, everything – sets, muscles, action, muscles, photography… and, did I mention, muscles? – was B-I-G!

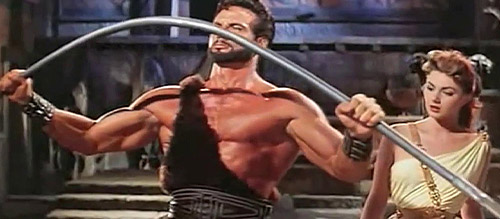

Steve Reeves as Hercules in Le fatiche di Ercole.

Usually (though not always) starring a scantily-clad American or English bodybuilder (such as Steve Reeves, Reg Park and Paul Wynter) as a figure from historical myth and legend (Hercules, Maciste, Samson or Goliath), the peplum, or sword-and-sandal picture, was supremely popular with Italian audiences between 1958 – the year of the release of Pietro Francisci’s film Le fatiche di Ercole (Hercules), starring Steve Reeves as Hercules – and the mid-1960s. In 1964, the international popularity of Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars) led Italian studios to focus on the production of westerns all’italiana (Italian-style Westerns) or ‘Spaghetti Westerns’ – a label that, like that of the peplum, was originally pejorative but which has since been adopted by fans of the genre. The western all’italiana and various other filoni assumed the mantle that had till that point been carried by the peplum.

On the subject of filoni, it’s worth reflecting on the extent to which Italian popular film production is dominated by the principle of the filone or ‘stream’/‘vein’/‘thread’. (Filone is the singular; filoni is the plural.) Roughly analogous to the concept of genre and the manner in which it is used to enable industry-like capitalisation on popular trends in English-language cinema, a filone is simply a strand of cinema whose popularity is exploited or mined ad infinitum, until the next filone takes hold. The concept of filoni led to Italian film production during the 1950s and beyond being dominated by specific, definable cycles/filoni – the peplum, the western all’italiana, Gothic horror films, mondo documentaries, the giallo all’italiana or thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller), the commedia sexy all’italiana (sex comedies), the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police picture), the jungle/cannibal adventure, and so on. The peplum was one of the first major, definable filoni of the Italian filmmaking boom that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. Like many of the subsequent filoni, such as the westerns all’italiana, the pepla were often co-productions featuring involvement – in terms of finance, crew, cast and sometimes locations – with production companies from other European countries: for example, France, West Germany, Spain.

As with later filoni, the pepla often featured cast and crew using adopted, Anglicised names in order to make the films seem more quintessentially ‘American’. (On A Fistful of Dollars, Sergio Leone famously used the Americanised name ‘Bob Robertson’, and Gian Maria Volonte was billed as ‘Johnny Wels’.) The Italian actor Adriano Bellini, winner of the 1961 ‘Mr Italia’ bodybuilding contest, was credited as ‘Kirk Morris’ in the pepla in which he appeared – such as 1961’s Il trionfo di Maciste (Tanio Boccia, credited as ‘Amerigo Anton’) and Maciste contro Ercole nella valle dei guai (Hercules in the Valley of Woe; Mario Mattoli), and Riccardo Freda’s Maciste all’inferno (The Witch’s Curse, 1962), on which Freda was billed as ‘Robert Hampton’. Even the Italian-American actor Lorenzo Luis ‘Lou’ Degni, the second US bodybuilder to be recruited by Italian producers to star in pepla (after Steve Reeves, of course), adopted a more ‘American’ sounding name, ‘Mark Forest’, for his screen appearances in pictures such as La vendetta di Ercole (Goliath and the Dragon; Vittorio Cottafavi, 1960) and Maciste l’eroe più grande del mondo (Goliath and the Sins of Babylon; Michele Lupo, 1963).

The popularity of the peplum in Italian cinema coincided with American interest in historical adventures that contained an element of fantasy, and many of the pepla were picked up by US distributors (for example, American International Pictures), who dubbed, rescored and cut the films for English-speaking audiences. Some of the films were cut or re-edited quite substantially. The US release of one of the last key pepla, Giuseppe Vari’s 1964 film Roma contro Roma, for instance, lost around ten minutes of narrative footage when it was released in the US by American International as War of the Zombies. (The film was released in the UK as Rome Against Rome.) Likewise, the US release of Riccardo Freda’s Maciste all’inferno was shorn of around 15 minutes.

Le fatiche di Ercole (1958)

The film usually cited as kickstarting the boom in pepla was Pietro Francisci’s 1958 film Le fatiche di Ercole, whose narrative focuses in part on the Argonauts’ quest for the Golden Fleece – placing Hercules front-and-centre in its retelling of the myth of the Argo and its crew. Distributed in the US by the canny Joseph E Levine – who had previously made a success of Gojira in 1956 by dubbing the picture, re-editing it and titling it Godzilla, King of the Monsters – Francisci’s film anticipated the popular Don Chaffey picture Jason and the Argonauts (1963), and its spectacular and memorable stop-motion effects by Ray Harryhausen, by half a decade. However, a casual viewer who is unaware of the films’ respective dates of production might be forgiven for thinking that Francisci’s film was a knock-off of the Chaffey picture. (In relation to the Francisci picture, Chaffey’s film inverts the story somewhat, throwing focus onto the character of Jason and making Hercules, played by Nigel Green, into a secondary character who memorably provokes the ire of the huge statue of Talos by stealing an enormous golden brooch pin, leading to the death of his friend Hylas.)

Thanks to a shrewd saturation marketing campaign conducted by Levine, Hercules made a startling $5 million profit in the US. Not bad for a picture for which Levine had paid a paltry $120,000 for the US distribution rights. In Italy, the pepla tended to be particularly popular in seconda visione (second run) picturehouses, with their often rowdy provincial working class audiences who would interact with the screen and treat the films almost as pantomimes. The popularity of these pictures was such that some of them, such as Vittorio Cottafavi’s 1961 picture Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide (Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis, aka Hercules and the Captive Women), were exhibited in 70mm formats.

Hercules may have initiated the boom in Italian production of pepla (upwards of 150 pepla were made in the late 1950s and early 1960s), and the willingness of English-speaking distributors to gather and distribute these films in territories such as the US and the UK – hence how Frank-N-Furter’s semi-oblique reference to the filone could be comprehended by the primary English-speaking audience for The Rocky Horror Picture Show. However, the first film to be labelled a ‘peplum’ in print was Riccardo Freda’s I giganti della Tessaglia (gli argonauti) (The Giants of Thessaly) in 1960, which also tells the story of the quest for the Golden Fleece, expanding the palette of the narrative to encompass other aspects of ancient myth – including adding Orpheus, played by Massimo Girotti, to the crew and having the Argonauts battle the Cyclops. Freda was, of course, along with fellow pepla filmmakers Mario Bava and Antonio Margheriti, one of the key figures in the popularity of Italian Gothic cinema of the 1960s, thanks to his work on films such as L’orrible segreto del Dr Hichcock (The Terror of Dr Hichcock, 1962) and Lo spettro (The Ghost, 1963).

Historical pictures had been made in Italy since the silent era: in the 1910s and 1920s, pictures about figures such as Maciste and Spartacus had been popular with Italian filmmakers and audiences. However, in the late 1950s the peplum experienced a surge in popularity that was most likely kickstarted by Hollywood’s decision to produce a number of historical epics in Italy, making use of the resources – both human and material – at studios like Cinecittà in Rome (‘Hollywood on the Tiber’, as it was nicknamed). Cinecittà had been founded by Mussolini in 1937, with the intention of reinvigorating domestic filmmaking. US studios made use of the expertise of Italian crew and resources during the 1950s and 1960s: a number of Hollywood epics were made at Cinecittà, including William Wyler’s Ben-Hur in 1959 and Joseph L Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra in 1963. The less prestigious Italian-made pepla often made use of the resources and industry that had been built around the production of US historical epics in Italy, sometimes reusing the impressive sets built for Hollywood productions, using the historical settings of these pictures in Ancient Greece and Rome as a springboard for more fantasy-oriented scenarios.

Reg Park in Ursus, il terrore dei Kirghisi (Hercules, Prisoner of Evil – 1964).

The pepla are strikingly diverse. The films, beginning with Le fatiche di Ercole, originally began as stories tied to Ancient Greece but expanded to Ancient Rome and then other, later historical periods: the label was ultimately applied to any sort of costume drama with a historical focus and an emphasis on plentiful action. Anything, in fact, into which a hunky former Mr Universe or other bodybuilding star (including former Tarzan, Gordon Scott) could be inserted; thus in export versions, films set during the era of the Mongol Empire and amidst the high seas of Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century piracy could and would be marketed as Hercules pictures. Italian filmmakers actually made 19 official Hercules pictures during the era of the peplum, though a number of other films featuring characters such as Maciste were rebranded as Hercules pictures for their release in English-speaking territories. So, for instance, Antonio Margheriti’s Ursus, il terrore dei Kirghisi (1964, most of which was reputedly directed by assistant director Ruggero Deodato, the future director of Cannibal Holocaust and House on the Edge of the Park), features Reg Park as Ursus and is set at some point during the high point of the Mongol Empire; in the English language export version, the character of Ursus was renamed Hercules and the film was retitled Hercules, Prisoner of Evil. Likewise, Luigi Capuano’s Sansone, contro il corsaro nero, released the same year, is essentially a swashbuckler that features former stuntman Sergio Ciani (most often known by his Anglicised name of ‘Alan Steel’), but was distributed in English as Hercules and the Black Pirate. (‘Sansone’, of course, became ‘Hercules’.)

As a general rule, any pepla distributed in English – either theatrically or via television screenings – that featured Maciste or Ursus as the protagonist and/or whose names appeared in the titles of the pictures, would be rebranded as a Hercules or, sometimes, Goliath picture. Names would be changed in the English dubbing, and the film’s title would be adjusted accordingly. For instance, Sergio Corbucci and Giacomo Gentilomo’s striking Maciste contro il vampiro (1961), which features Maciste (Gordon Scott) in a fantastical plot that sees the hero confronting a powerful vampire (Kobrak, played by Guido Celano), was rebranded in English as Goliath and the Vampires. Corbucci would go on to become one of the most distinctive and political directors of westerns all’italiana, with the brutal Django in 1966, and the striking snowbound Il grande silenzio/The Big Silence in 1969; there are touches of the unflinching sadism of Corbucci’s Westerns in Maciste contro il vampiro, notably in a sequence in which a village is ransacked and the camera shows a number of gruesome touches – memorably a corpse of a villager whose foot is tethered by a rope to the rafters of a burning building. The building collapses, and the corpse falls into the flames; Corbucci holds on the very realistic-looking limb long enough to imprint the scene into the viewer’s memory.

The majority of pepla feature a recurring, easily identifiable set of narrative motifs. In the majority of the films, the hero demonstrates his brute strength in the film’s opening sequence. In Le fatiche di Ercole, Hercules opens the film by ripping up a tree and using this to stop a tearaway horse and carriage carrying Princess Iole (Sylva Koscina). ‘I thank the gods for providing me with such a strong man when I needed him!’, Iole swoons. In Maciste contro il vampiro, Maciste is introduced moving an enormous boulder from the middle of a field that he is ploughing and then, hearing cries for help, rescues a young boy – the brother of his fiancée Guja (Leonora Ruffo) – from a giant underwater monster. In some of the films, Hercules/Maciste/Samson/Goliath is a wandering hero, like the ronin of Japanese samurai pictures (or like the anti-heroes of many later westerns all’italiana, including Eastwood’s ‘Man with No Name’ in the Leone pictures), who comes across an oppressed and/or terrorised community, using his strength in servitude of liberation. (This no doubt spoke very profoundly to audiences for whom Mussolini’s dictatorship was within fairly recent memory.) Our hero usually encounters a plot which involves an evil, powerful woman – often assisting, or being assisted by, an equally powerful and evil male figure – whose self-interest contrasts with a good, pure-hearted female character. The evil woman invariably attempts to seduce the hero, but often falls in love with him – sometimes redeeming herself in the process. In Maciste contro il vampiro, for instance, Maciste encounters a sorceress, Astra (Gianna Maria Canale), who serves the film’s antagonist, the vampire Kobrak (Guido Celano). Astra tries to seduce Goliath in order to persuade him not to confront Kobrak.

Maciste contro il vampiro (Goliath and the Vampires, 1961)

From Le fatiche di Ercole onwards, the pepla emphasised mythology and featured inventive, though sometimes unconvincing, effects – from costumes, rubber suits and simple use of forced perspective to more complex stop-motion and compositing effects – in order to render fantastical creatures and scenarios. As the filone progressed, and filmmakers were presumably looking for ways of differentiating their pictures from other pepla, some of the pictures featured an increasing emphasis on fantastical elements. Some of the later pepla bordered on the absurd. Antonio Leonviola’s 1961 effort Maciste, l’uomo più forte del mondo (‘Maciste, the Strongest Man in the World’, distributed in the UK as The Strongest Man in the World and in the US as Mole Men Against the Son of Hercules) features a Robert E Howard-like plot in which Maciste (played by Mark Forest) witnesses a ritual sacrifice conducted by a strange group of men, the subterranean Mole Men, who are dressed entirely in white; their victim is Bango, played by the black Caribbean bodybuilder Paul Wynter. In the year of the Freedom Riders and their defiance of Jim Crow laws, provoking the ire of the Ku Klux Klan in the Southern States of the US, it’s hard to imagine that the staging of this sequence was not taken, if not intended, as a dry comment, on the part of the Italian filmmakers, on the activities of the Deep South’s Klansmen and the embedded, and increasingly exported, racism of so much mainstream US culture of the period. Maciste rescues Bango, and the pair team up to take on the Mole Men, who are terrorising the region, abducting locals and using them as slaves to power their huge underground machinery.

Giacomo Gentilomo’s 1964 picture Maciste e la regina di Samar (‘Maciste and the Queen of Samar’, released in the US as Hercules Against the Moon Men), the final film of its director, sees Maciste (played by Sergio Ciani/Alan Steel) arriving in the kingdom of Samar and discovering that Queen Samara (a pouting, sassy Jany Clair, who throughout the picture sports a distinctively mid-Sixties range of hairdos) has made a pact with a group of extraterrestrial beings who have taken residence in a nearby mountain: the community’s children and young people are regularly sacrificed to the ‘Moon Men’ in the mountain in order to maintain Queen Samara’s reign. ‘Only arrogance and limitless pride animate that woman’, one of the characters says, ‘along with unrestrained ambition’. The queen has a ‘good’ sister, Billis (Delia D’Alberti), whose selflessness contrasts with her sister’s commitment to her own self-interest. Eventually, Maciste takes on the Moon Men, whose shadowy netherworld is communicated via the use of low-light photography and green lighting gels. Hercules’ physical prowess impresses Queen Samara, who orders Maciste to be taken to her quarters, where she seduces him and presents him with a drink containing a love potion. Luckily, Maciste has been forewarned of the queen’s use of this potion, and disposes of it discretely, enabling him to eliminate the Moon Men, end the reign of the wicked Queen Samara and rescue Princess Billis and her lover, Prince Darix (Jean-Pierre Honoré). The film is a visually striking picture, especially as it moves into the subterranean lair of the Moon Men, but its narrative is little more than big screen panto.

With the late-period shift towards more fantasy-oriented scenarios in mind, it is worth considering in more detail two specific pepla made by directors who, for English-speaking cinephiles are more commonly associated with their work in the filoni of Gothic horror and thrilling/giallo all’italiana: Mario Bava, the director of La maschera del demonio (Black Sunday/Mask of Satan, 1959) and Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), and Riccardo Freda, the director of the aforementioned L’orrible segreto del Dr Hichcock and gialli such as A doppia faccia (Double Face, 1969).

Directed by Freda in 1962, Maciste all’inferno (‘Maciste in Hell’) shares its title with a 1925 silent film directed by Guido Brignone. Brignone’s film was the last Maciste picture made during the silent era, and features Maciste, played by Mussolini favourite Bartolomeo Pagano, being enticed into the underworld by Barbariccia, an envoy of Pluto himself. In Hell, Maciste is seducted by Proserpina, Pluto’s wife, and Luciferana, Pluto’s stepdaughter. The title of Freda’s 1962 picture no doubt deliberately pays tribute to Brignone’s haunting, inventive film. However, Freda’s Maciste all’inferno was released in the US, where the Brignone film was largely unknown, as The Witch’s Curse, shorn of almost 20 minutes of footage. (The film seems not to have been released at all in the UK.) Interestingly, as the English dub for this picture was produced in Italy, this was one of the few Maciste films of the period in which the protagonist kept his name in the version of the film released in English-speaking territories: although Maciste was the most popular character in Italian pepla, the name was largely unknown to English-speaking audiences, this of course being owed to how many dubs had changed Maciste to Hercules, Samson or Goliath across previous releases.

Maciste all’inferno (The Witch’s Curse, 1962)

Freda’s Maciste all’inferno opens in Scotland in 1550, where a witch, Martha, is burnt at the stake. Unlike the alleged witches in, say, Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968), there is no doubt about Martha’s association with witchcraft. The Scottish setting is interesting, of course, given that the stated execution in the film is set prior to the 1563 Witchcraft Act – which made the practice of witchcraft a capital crime. (Documentation suggests that the first – failed – witchhunt in Scotland took place in 1568.) Martha places a curse on the town, and we are taken to a hundred years later, 1650. In the interim, in terms of the history of witch-hunting in Scotland, James VI wrote Daemonologie after visiting Denmark in 1589 to marry Princess Anne – and provoked in part by the North Berwick witch trials of 1590, after which a number of people were executed for allegedly attempting to murder the king by poison and casting spells to cause storms that would sink his ship.

In 1650, the townsfolk live under fear of Martha’s curse. Driven by this fear, the locals torment and execute any woman believed to be associated with witchcraft, hanging them from the charred tree that marks the spot at which Martha was burnt. When a woman named Martha (Vira Silenti) arrives in the town to marry a young squire, Charley (Angelo Zanolli), the townsfolk are convinced she is a reincarnation of the witch. They vow to execute her at the stake and imprison her. However, conjured out of nowhere, an amnesiac Maciste (Kirk Morris) arrives on horseback. Dressed in his loincloth, he is hugely incongruous in the 17th Century Scottish setting. Maciste bends the iron bars of the prison in which Martha is held and fights off the menfolk, picking them up like toys and hurling them. Maciste discovers that the only way to break the witch’s curse that hangs over the area is to venture into Hell – by ripping up the aforementioned charred tree, thus uncovering a cavern which leads to the underworld.

Maciste here has no memory, and part of the story involves his struggle to regain awareness of who he is. The film is part of a broader narrative which encompasses the Maciste films made by Panda Film: the previous film in the series was Mario Mattoli’s comedic Maciste contro Ercole nella valle dei guai (Hercules in the Valley of Woe), which features a plot involving two 20th Century characters – the comic duo of Franco (Franchi) and Ciccio (Ingrassia) – who are catapulted back in time via a time machine and encounter both Maciste and Hercules. (One wonders if this Franco and Ciccio comedy was somehow an inspiration for Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure.) Taking place immediately after this picture and its time travel plot, Maciste’s appearance in 17th Century Scotland perhaps makes a little more sense.

In the underworld, Maciste is able to regain his memories, leading to lengthy ‘greatest hits’ style flashbacks from various Maciste films – including one made by Freda, Maciste alla corte del Gran Khan (Samson and the 7 Miracles, 1961), in which Maciste was played by Gordon Scott, an actor predominantly known for his role as Tarzan. (Cue much confusion from the audience as they watch Kirk Morris’ Maciste recall his adventures as Gordon Scott.)

Maciste All’inferno (The Witches Curse, 1962)

Hell is dominated by the groans of the damned and scenes of torture ripped from the pages of Dante’s “Divine Comedy”. In a chamber are dozens of souls, forced to hold up huge boulders; Maciste attempts to help one of these, an elderly man, but finds even his brute strength defeated by this endless task. Nevertheless, for most of the film, Maciste is able to confront the supernatural by the simple deployment of his sheer strength, highlighting the extent to which the Italian pepla suggested that problems could be solved with muscles, brute strength and an ironclad will. (This has led some commentators, such as Richard Dyer, to suggest that the peplum was Italian culture’s way of confronting its fascist past, with parallels sometimes drawn between the kind of virility and strength represented by Maciste and the public image projected by Mussolini.) On his first entrance into Hell, Maciste is confronted by a lion. He fights and defeats it. Watching this event via supernatural means, the witch and an accomplice observe, ‘That poor fool’s [Maciste] muscles and courage will never be sufficient. He can strangle a lion but there’s no man on Earth who can conquer the Devil!’ (This observation echoes a line in Le fatiche di Ercole, in which one of the characters notes of Hercules that, ‘You can tell from his eyes that he’s as pure as sunlight, and his strength is a challenge to all evil’.) In the English version of Maciste contro il vampiro, the sorceress Astra suggests, naively, that ‘Goliath [Maciste] is very strong, but his strength is to no avail against magic and witchcraft’. Similarly, Vittorio Cottafavi’s Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide sees Hercules’ ally Androcles (Ettore Manni), who has been brainwashed by Queen Antinea of Atlantis (Fay Spain), tell Hercules, ‘You are mad if you think you can combat the might of Atlantis with the pitiful strength of your muscles’. (Little does he know…)

In the underworld, Maciste encounters various characters who help him to regain his memories. ‘Do you see what you can accomplish when you have strength and courage tethered to your own free will?’, he is told. Maciste’s journey becomes increasingly surreal. He meets Prometheus (Remo De Angelis), who is tethered with chains to a huge boulder, eagles tearing out his entrails… forever. Following this, he encounters a stampede of bulls, and stops them by ripping up a huge stalagmite and using this to block their path.

Like many other pepla, Maciste all’inferno sees the ‘bad’ woman (the witch, Martha) falling for the musclebound hero and ultimately redeeming herself. ‘I thought that [love] was all finished’, the witch says, ‘I tried to corrupt him [Maciste] with my witchcraft and charm’. Of course, the curse is lifted, and Maciste exits Hell, rescuing Martha as the villagers demonstrate their gratitude.

In its depiction of Maciste’s journey into the underworld, Maciste all’inferno offers a vivid depiction of Hell that underscores Freda’s reputation as a director most commonly associated, at least for English-speaking cinephiles, with Italian horror pictures – actually a small part of Freda’s career, but certainly the genre in which he pursued his most distinctive work and which, in the 1960s and 1970s, he came to represent alongside contemporaries such as Antonio Margheriti. Likewise, Mario Bava’s Ercole al centro della terra (Hercules in the Haunted World, 1961) features a similar journey into Hell for its titular character, in a film by a director most often identified for his later work in the horror genre.

Reg Park as Hercules in Ercole al centro della terra (Hercules in the Haunted World, 1961).

In Ercole al centro della terra, Reg Park plays Hercules, who travels with his friend Theseus (Giorgio Ardisson) to the Kingdom of Ecalia, where Hercules hopes to be reunited with his lover, Princess Deianira (Leonora Ruffo). At the palace, he is informed by Deianira’s uncle, Lyco (Christopher Lee), that his beloved has ‘a great illness’ and has lost touch with the world around her. In reality, Deianira is being held prisoner by Lyco, who practices necromancy; her father, King Uriteis, having recently passed away, Deianira is the heir to the throne of Ecalia, and Lyco plans to murder her and drink her blood – stealing the throne which is rightfully hers. In this, there is more than a touch of the story of Richard III (at least, the version of Richard III’s story which flattered the Tudor era), with Lee’s haircut and costume resembling that of the last Plantagenet king – particularly as represented in Olivier’s then-recent 1955 screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. Like Richard III was alleged to have murdered his young nephews – the rightful heir to the throne, Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York – in order to seize the throne following the death of Edward IV, Lyco holds his niece Deianira captive and plots to murder her so that he may control the Kingdom of Ecalia.

Under the spell of Lyco, Deianira notes poetically that ‘We do not even know ourselves. Only he who commands us. He who is our master, who we must obey’. Again, one might think of Italy’s fascist past and the authoritarian rule of Mussolini. Wrapped in a sheen of fantasy, Bava’s Hercules picture is strikingly allegorical. The land, Lyco tells Hercules, was cursed when King Uriteis drove the evil that previously plagued Ecalia ‘to the land of the dead’. The curse will only be lifted when Uriteis last descendant, Deianira, is dead. ‘How can one fight against shadows?’, Lyco asks Hercules, ‘Fight against winds or lightning? Against the terrible storms that batter the earth?’

Hercules travels to speak with his oracle, who sits cross-legged in a dark chamber filled with water; she wears a mask and speaks in riddles whilst performing what can best be described as a series of conceptual dance moves using only her arms, as lights with primary coloured gels hit her body. ‘Though evil descends upon the earth like a darkening of the sun, it can disappear as quickly’, she tells him mysteriously. Hercules pleads with his father, the god Zeus, to help him combat this evil and release Deianira from the spell which binds her. Hercules offers his immortality in exchange for an opportunity to aid his beloved. ‘Dare you venture beyond the portals of Hades’, the oracle asks Hercules, ‘to the domain of the god Pluto?’

Christopher Lee and Leonora Ruffo in Ercole al centro della terra (Hercules in the Haunted World, 1961).

Hercules enlists the help of his friend Theseus and a bumbling, comic sidekick, Telemachus (Franco Giacobini). To enter the underworld they must steal the magic ship of Sunis and sail to the kingdom of Hesperides, where they must eat the Golden Apple from the Sacred Tree. In Hesperides, Hercules and his companions are faced with a community consisting solely of women, led by Aretheuse (Marisa Belli). By collecting the Golden Apple, a task which Aretheuse believes is not possible, Hercules liberates the women of Hesperides from the controlling grasp of Pluto; however, this is not before the women, manipulated by Pluto’s will, have set a trap for Theseus and Telemachus, who are attacked by Procrustes, a creature made from stone. (Like the Procrustes of Greek myth, this Procrustes threatens to stretch the pair on a bed of rock.) Hercules interrupts and, picking up Procrustes, hurls the stone creature against a wall of the cavern, causing the wall to partially collapse and revealing an entrance to the underworld.

In entering, Hades, Hercules and Theseus discover that they are confronted by a series of illusions, including a sea of fire, designed to prevent them from moving forwards. Hacking at vines that block their path, they hear the screams of the damned and realise the vines are bleeding. In the centre of this labyrinth is a black stone that is surrounded by white hot flames and protected by lava. This stone will free Deianira. Hercules and Theseus use the vines to create a rope-crossing across the lava, but Theseus falls and is apparently killed. However, this is also an illusion, and when Theseus awakens he encounters a beautiful woman, Persephone (Evelyn Stewart), the daughter of Pluto. Hercules and Theseus are reunited, and with Persephone’s help, Hercules and his companions escape from Hades and return to Ecalia in time to rescue Deianira.

However, before Hercules can confront Lyco, he is forced to fight his way through hordes of the undead who are conjured to life by Lyco’s necromancy, clawing out of their graves and climbing from their tombs. This sequence is striking, especially for the manner in which these undead figures predate the ghouls and zombies of post-Night of the Living Dead (George A Romero, 1968) horror movies – especially those of Italian zombie pictures such as Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (Zombie Flesh Eaters, 1979). Certainly, some of this imagery, including the undead wrapped in their shrouds and the masked appearance of Hercules’ oracle, seem to have worked its way into Lucio Fulci’s later sword and sorcery picture Conquest.

Ercole al centro della terra (Hercules in the Haunted World, 1961)

Ercole al centro della terra emphasises the dualisms that are evident in a number of the major pepla: the sanctity of the world above ground versus a subterranean world populated by monsters and/or duplicitous figures of authority; good versus evil; light versus darkness; strength versus cunning. Luckily, the Bava film survives on digital home video in its original widescreen version, which enables the viewer to appreciate the superb photography and lighting, and Bava’s skill in telling a story visually – one of this filmmaker’s great strengths. The film features much staging in depth, with full use of the widescreen frame to create juxtapositions between foreground and background action. There are also some incredible visual effects involving matte work and impressive props and sets which are made even more impactful by the careful use of lighting – including the use of coloured gels that made so many of Bava’s colour pictures so distinctive – and negative space. Sadly, on the other hand, like many of Freda’s films, Freda’s equally interesting Maciste all’inferno has been badly served by digital home video releases in English-speaking territories, with the only DVD release being of a panned-and-scanned full screen print of the US release version, which is missing about a quarter of an hour’s worth of footage. Fortunately, the full-length cut of Masciste all’inferno has been released in widescreen on DVD in France – but in a release which, frustratingly, isn’t English-friendly.

One of the more notable late examples of the peplum, Giuseppe Vari’s Roma contro Roma was one of the final films of the peplum boom. Noticably absent from the film is the muscular hero of the majority of pepla. The film focuses on a centurion, Gaius (Ettore Manni), who is tasked with journeying to a region that is governed by the pretor Lutetius (Mino Doro), but in which a centuria has disappeared along with an amount of treasure. Gaius is warned that the region is dominated by a necromancer, Aderbad (John Drew Barrymore), who is secretly in league with Lutetius. (The pair have secreted the treasure, and Aderbad has taken the corpses of the slain Roman legionnaires, using them in his black magic – resurrecting them and then melding them with the stone walls of the cavern that he occupies, like Han Solo frozen in carbonite in the much later The Empire Strikes Back.) Though the Romans criticise the superstitions of the locals, prior to making his journey Gaius vows to sacrifice a lamb to Jupiter, so that the god will offer him protection during his quest. The irony of this moment is presented quietly for the alert viewer, Vari not drawing attention to it. (Later, Gaius fails to note the irony in his assertion that ‘A consul of Rome must not believe in magic. A consul of Rome must not believe in fantasy. He must believe in what he can see, or feel, or touch’.) This moment is the first major indication of this film’s critique of the hypocrisies of colonialism, which seems strikingly relevant in the era of the Second Indochina War and the proxy war in Vietnam that, only a year or two later, would lead to direct US military involvement in that part of the world. In fact, though made prior to the peak of the Vietnam War Roma contro Roma feels very much like an allegory for it – not dissimilar to some of the revisionist Westerns of a decade later, such as Michael Winner’s Chato’s Land (1972) and Robert Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid (1972) – though was likely just as much intended as a comment on any form of mid-Twentieth Century colonialism.

Gaius discovers that Lutetius rules the region with an iron fist; Gaius interrupts the whipping of an elderly peasant, ordered by Lutetius as a means of punishing the locals for the supposed theft of the treasure. ‘If Rome wants a tribute to her, it’s not through softness that you’ll get it from these people’, Lutetius tells Gaius, ‘They hate us!’ ‘They’ll hate us even more if we treat them like beasts’, Gaius responds – another dry comment on the imperialist mindset which would feel increasingly relevant in the years that followed the film’s original release, during the US battle for the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people in defeating the North Vietnamese insurgency. In a later sequence, after Aderbad kills Lutetius and frames Gaius for the murder, in retaliation for the death of the pretor, Roman centurions tear through a settlement, burning the villagers’ homes and murdering men, women and children. In a shot that strikingly resembles a similar moment in Ralph Nelson’s Western Soldier Blue (1970), which used the 1864 Sand Creek massacre of Native Americans by the Third Colorado Cavalry as an allegory for the then-recent My Lai massacre, a woman carrying a baby is struck down by a sword-wielding centurion. The film climaxes with Aderbad resurrecting the slaughtered legionnaires, directing them to attack the living Roman soldiers, observing in reference to one of his zombies, ‘Look at him! He is alive but has no will. He is the perfect warrior, for he is immortal. No-one could kill him twice’.

John Drew Barrymore in Roma Contro Roma (War of the Zombies, 1964).

Roma contro Roma’s release came in the same year as the release of the picture which kickstarted the next big trend in Italian popular cinema, Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964). Achieving popularity with international audiences, Leone’s film would initiate the boom in production of westerns all’italiana. Leone had of course begun his career as a director working on pepla: his first work as a director was on the 1958 picture Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (The Last Days of Pompeii), starring Steve Reeves, when the film’s original director, Mario Bonnard, fell ill. Leone’s ‘proper’ directorial debut was the memorably epic Il colosso di Rodi (The Colossus of Rhodes) in 1961. It’s easy to see in Per un pugno di dollari, and many of the subsequent Italian Westerns by Leone and other directors, a sense of myth and the folkloric qualities of the pepla being channeled into a Western setting.

The international popularity of pepla, particularly with US distributors, paved the way for other Italian products to be marketed to English-speaking audiences – from the westerns all’italiana of the 1960s to the gialli and poliziesco films of the 1970s. These films also acted as a reference point for the boom of production in sword and sorcery films during the 1980s – in Italy (Joe D’Amato’s Ator in 1982; Lucio Fulci’s Conquest in 1983; Ruggero Deodato’s The Barbarians in 1987) and the US (John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian and Don Coscarelli’s The Beastmaster, both in 1982). Nevertheless, the peplum is often overlooked in discussion of Italian popular cinema, in favour of later filoni – such as the western all’italiana and giallo all’italiana. However, what is notable about the pepla themselves is – aside from the formulaic nature of many of the narratives – just how allegorical the stronger (pun intended) pepla are. If the original pepla of the silent era – particularly Bartolomeo Pagano’s performance as Maciste – had been a model for Mussolini’s dictatorship, the pepla of the late 1950s and 1960s often seem like a way of exorcising Italy’s fascist past. No matter how many times the villains assert that the respective musclebound heroes of the films will not be able to defeat evil through strength alone, they are proven wrong. Many of the films take place in lands that are cursed; Bava’s Ercole al centro della terra, for example, is set in the Kingdom of Ecalia, which is overseen by the cruel Lyco – a vampire and necromancer willing to murder his own niece in order to maintain his authority. The land is cursed by the influence of a dark force angered by the late King Uriteis’ attempts to eradicate it. The parallels with post-fascist Italy seem quite direct, and of course these themes would work their way into many westerns all’italiana, which often take place in towns haunted by past traumas and dominated by authoritarian figures – for example, Giulio Questi’s offbeat Sei sei vivo spara (Django Kill!, 1967), whose depiction of a town dominated by a sadistic black clad hoodlum and his fascist henchmen was, Questi claimed, inspired by the director’s experiences as an anti-fascist partisan in the mountains of Italy during the Second World War.

On the other hand, it’s difficult not to find a much more simple, childish delight in the camp, pantomime nonsense of many pepla: this writer dares anyone to watch the English-dubbed version of Ercole alla conquista di Atlantide and not laugh at the repeated, po-faced discussion by characters of ‘the Rock of Uranus’. (Fnarr-Fnarr. The English dubbed version of this picture could quite easily have been released as a Carry On… picture. Carry on Beefcake, perhaps.) The pepla are often dismissed as pictures that live or die on the size of the muscles of the beefcake actors that star in them, or the provocative costumes of their female counterparts. In the pepla, bodies are pulled apart but also held together by pure physical strength and force of will; these are, of course, both the bodies of individuals but also, increasingly, the notion of the body politic – the body as metaphor for society. In the face of what is often supernatural, authoritarian cruelty, bonds are made that bridge superficial differences between individuals. Perhaps ultimately, what is so fascinating about these films is the manner in which the absurd and the profound, the concrete and the abstract, the historical and the fantastical, often coalesce within their narratives.

Written by Paul A J Lewis

You can support Paul A J Lewis in the following places:

Website – paul-a-j-lewis.com

Twitter – @Krycek_Facility