Edward Scissorhands (1990) Review

Edward Scissorhands (1990)

Director: Tim Burton

Screenwriter: Caroline Thompson

Starring: Johnny Depp, Winona Ryder, Dianne Wiest, Anthony Michael Hall, Kathy Baker, Alan Arkin, Vincent Price

The realisation that it has been thirty years since Edward Scissorhands’ first release is indeed staggering. Back when Tim Burton was the unofficial king of all things gothic, his 1990 film was a must-watch for all teenage girls, especially those who could identify with being outcasts or being a part of outcasted subcultures. Generations have passed since then however, and in changing times, as music has evolved from The Cure and Nirvana into less brooding alternatives, and young people have sought solace from increasingly volatile real world politics through the colourful fantasy of superhero cinema and video games; does Edward Scissorhands remain the fresh serving of alternative entertainment it once was, or is it a relic of a laughable by-gone era? Perhaps just as importantly, does anyone even care about Tim Burton anymore?

Since the day it first hit cinema screens, Edward Scissorhands has time and time again been described as a modern day fairy tale, and indeed the plot strikes a resemblance to tales of yore such as Brothers Grimm’s “Hans my Hedgehog” and Gabrielle-Suzanne de Barbot Villeneuve’s “Beauty and the Beast”. It could also be interpreted as a modern update of the Frankenstein story. Yet, amongst this flurry of comparisons, Burton’s story remains quintessentially unique. It is, after all, a simple yet curious tale about where snow comes from.

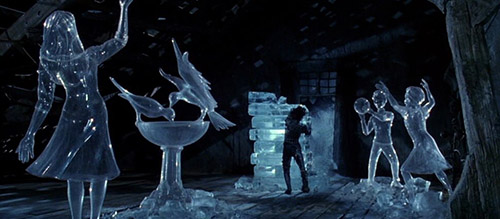

The titular Edward (Johnny Depp in perhaps his second most iconic role behind that of Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean) is a man who was created by an Inventor (Vincent Price) in a mansion overlooking a pastel-coloured suburban haven. The elderly Inventor raised Edward to be a genteel and sweet man, but died before finishing him, leaving Edward with a set of huge razor-sharp scissors for hands. In Edward Scissorhands, Edward remains alone and incomplete in the mansion until (of all things) an Avon Representative, Peg Boggs (Dianne Wiest), comes knocking on the door. Overwhelmed with compassion at the sight of the pale and scarred Edward, Peg decides to take the awkward and unusual man down to the suburban haven below in the hope of forging a better life for him. Within this epitome of late 20th century Middle America, Edward seems to discover a new found love and acceptance as he becomes a figure of curiosity and inspiration through his unassuming character and moreso through his creative (and useful) talent channelled through his scissor-hands. But just as soon as Edward and his hands become an object of adoration and praise, he is transformed into a figure of fear and revulsion. Although his scissor-hands are a source of beauty, they bear the constant danger of damaging the things and people around him.

By no means is Edward Scissorhands the beginning of director Tim Burton’s journey as an auteur; our King of the Goths has directed movies and shorts with his quirky visual style and weirdness since the 70s. This particular film is most definitely one of the most important entries in his oeuvre however, easily being one of the most cherished of his works. Scissorhands increased Tim Burton’s appeal, as it helped to define key factors that have ensured the continuing popularity of the Burton “brand”. We had a continuation of the casting of Winona Ryder following her star turn in Beetlejuice, helping to establish her as the edgy leading lady of the era, and Danny Elfman was again chosen as musical composer, resulting in a haunting score that is so characteristic of Burton’s work that any Burton film would be incomplete without the composer’s influence. It is also the beginning of Burton’s partnership with Johnny Depp, which has spanned to this very day. Yet, amongst the tried and tested tropes that are oh so typical of a successful Burton directed piece, it is the wholly unique qualities of Edward Scissorhands that make it a stand-out release in the director’s filmography. Out of a body of work defined largely by its visually driven and stylistic directorial intent, Edward Scissorhands rises up with a very clear and loud message.

Just like many Burton films, Edward Scissorhands dances the borderline between the ordinary and fantasy – a reality very much like our own is presented, but one into which a little magic bleeds. With a career shaped within animation, Burton makes full use of a movie’s aesthetics to create its internal universe, and Edward Scissorhands is no exception to this with its day and night duality of the gothic mansion (which wouldn’t be out of place in a 1930s Universal Pictures Horror) and the vivid yet bland architecture of the surrounding suburbia. Overall, the design is very much an over-exaggeration, and initially it would be easy to worry that the film would be a very cartoonish affair. However, the appropriate amount of whimsy is achieved, which can be attributed to Edward Scissorhands’ astute observation of human character.

Burton’s thorough understanding of human behaviour means that Scissorhands manages to encapsulate the deep fantasies found within a teenage girl’s heart: that is the innate desire to be adored. Through High Schooler Kim (Winona Ryder) – Peg’s daughter – does many a young girl’s greatest desire come true as she becomes the subject of Edward’s devotion. In a world of mediocrity, she wins the affections of the most incredible being that she will ever know in her entire life. The love between Edward and Kim is, as perhaps should be expected given their on-screen age, very much adolescent – upon repeated watches you do question what caused Edward to fall so hard for Kim; the reasoning is so thin it’s almost a plot discrepancy. Even so, it’s a tale as old as old as time – to be touched by greatness so as to become great yourself – and what becomes clearer and more greatly appreciated from Edward Scissorhands’ world of deadly accurate caricatures of human life is the story that indeed remains relevant thirty years on from its first release.

Whether or not we include romance and magic in the analysis of Edward Scissorhands, it remains quite clear that this is a film that is essentially about being “different”. It’s an excellent piece of satire with regards to late 1980s Middle Class America – consumerist, shallow and utterly devoid of meaning – and of course all the familiar faces of the era are present in glorious exaggerated form (Alan Arkin as Peg’s husband Bill is very much the typical not-quite-present, half-hearted father figure; Anthony Michael Hall manages to break his high school geek type-casting as the villainous and boorish Jim; Kathy Baker steals the show as the eternally bored housewife, always overly eager for adultery; even Peg fits a not-so-flattering role – she has the noblest intentions towards Edward but is still deeply affected by peer pressure and consequently some of her decisions are not in Edward’s best interests), but woven into its every piece of construction is the thought to present what it’s like to feel and/or be different. As Sara Ann of The Mighty suggests, Edward Scissorhands is a film about disability.

“Edward tries to succeed and fit in, but he finds himself trapped by numerous barriers and challenges.”

Like so many of those tone deaf social media posts in which a person living with a disability is hailed as an “inspiration”, Edward is marvelled at like a museum exhibit (or even a sideshow) and is even fetishised by the townswomen. He is failed in his disability.

Many of the microaggressions are genuinely saddening, and the sorrow furrows deeper when we realise their presence in our own world. Edward’s talents are constantly used (and even abused at some points), with his exceptional hedge trimming, dog grooming and hair styling going largely unpaid for – and then the real kicker is that he’s rejected the financial assistance he needs to start his own legitimate business. We take a journey of frustration, witnessing the lack of real accommodation for Edward’s needs – despite the Boggs’ attempts at inclusion, it’s clear Edward’s stay with them is not comfortable for him. Stand out moments are Edward’s saga with the water bed that offers him no restful sleep (remember, razor sharp hands), and Bill offering him a whisky (after about two minutes of listening to Edward failing to take a drink does he remember to offer him a straw). Then, the tide turns against Edward as he becomes feared and loathed – a whole section of academia can be dedicated to humanity’s treatment of, and the media’s depictions of, people with disabilities, in which physical disabilities are often equated with having a poor character or, worse, with being outright evil. As Tim Burton trashes this harmful stereotype, his decision to display Edward’s fear of the police still hits hard today with the sobering knowledge of the judicial system’s treatment of those with mental health issues (an article from The Washington Post reported that the incidences of mental illness in those executed on death row is much higher than that of the general public).

In being able to articulate these extremely serious and legitimate parallels with real life, Edward Scissorhands really is Tim Burton’s filmmaking triumph, with this now thirty year old film truly establishing the director as one of Hollywood’s most iconic filmmakers. Not only does Burton provide the perfect escapism with this movie’s magic, but he advocates for the dignity and the intrinsic value of all human life. Just because it’s not evident to our prejudiced eyes, it doesn’t mean it’s not there – surely Edward being the one responsible for the Christmas snow is proof enough.

20/24

Recommended for you: Tim Burton Movies Ranked