Where to Start with Michael Haneke

Austrian writer and director Michael Haneke has crafted a canon of cinema that traverses the darkest depths of the human psyche against the backdrop of the monotonous every day to create boundary-crossing, innovative experiences.

Haneke has often expressed his cinematic motivations as reflecting the horrors that can hide amidst the most humdrum of circumstances. Haneke’s scope of work travels back to the late 1980s with his debut feature, The Seventh Continent (1989), which follows a seemingly ordinary family over three years before bleakly disrupting the mundane narrative with a shocking, fatal finale. This mingling of dullness with terror would become a distinct emblem within his next feature, Benny’s Video (1992), another recital of death against commonplace domestication.

Thereafter, Haneke developed this sense of indirect insidiousness to accommodate narratives rich in social commentary, particularly surrounding colonisation, war, and increased violence within mainstream media. This aspect of societal and cultural motivations is admirable, but without Haneke’s distinct ‘style’, his work would be all ‘substance’. Haneke’s efforts to develop film form can only be described as cinematically beguiling. Many of his films, such as The Piano Teacher (2001) and Happy End (2017), are immersed with stunning cinematography and moving scores to transfix the viewer and create an alarming yet inviting world. Paying close attention to Michael Haneke’s filmography highlights his multifaceted portfolio in which every entry is as meaningful as it is hypnotic.

Haneke’s tenacious grip on unravelling family dynamics and corrosion of the self has made him a regular winner at the Cannes Film Festival and César Awards. With such acclaim and admiration adorning his dense cinema catalogue, breaking down his work can be quite a task. In honour of this distinguished filmmaker, here is The Film Magazine’s guide on Where to Start with Michael Haneke.

1. Funny Games (1997)

Funny Games and the Victimisation of the Audience

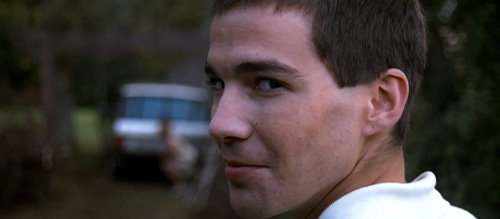

The Schober family take to their lake house for their annual summer getaway, only for two men, Paul (Arno Frisch) and Peter (Frank Giering), to appear unannounced and unwelcome. The unexpected encounter soon takes a deadly turn as the pair decide they want to play a game.

Funny Games puts Michael Haneke’s rigorous approach to creating cinematic tension into practice. The entire runtime is an exercise devoted to testing the borders of film and reality, and employing brutal savagery to invoke harsh discussions of complicity and the role of spectatorship. Invoking Funny Games‘ lesson in austerity is Haneke’s use of progressive camera work, including Peter and Paul’s continuous breaking of the fourth wall. Disrupting the narrative by forcing sudden conversations between a character and the viewer is a widespread but uncommon device to pull the curtain of fantasy back on the on-screen cruelty. The interrupting fourth-wall segment allows the killer duo to speak to their audience, forcing the viewer to not simply watch the violence with a cloak of invisibility but instead join in, participate, and engage not with the victims but with the villains.

Michael Haneke understands cinema’s power, its hold over its viewer, how the moving image can be utterly ensnaring. Further suspending the barriers of screen and reality is a scene involving Peter being shot point blank, a presumed fatal blow to the chest. However, in the most bizarre sequence of events, Paul picks up a TV remote. He rewinds time, with Haneke maintaining a stagnant long shot of the characters performing their actions in reverse, bringing Peter back to life. It is an astonishing segment that instigates the dense theology that Funny Games espouses – Peter and Paul (acting as violent mediators) are in control, and the viewer has to watch idly as Haneke toys with the urge to watch a self-proclaimed hopeless and pointless piece of cinema.

Moreover, with the self-referential, metafictional tones in the film’s peripheral, Haneke sets out to critique the human condition, and the strange catharsis spectators crave from nihilistic, loathsome media.

2. Caché (2005)

Just as Funny Games and its later shot-by-shot remake of the same name (2007) highlight, Michael Haneke’s stylistic sensibilities are rife with transcending the borders of fiction and infusing dark analogies.

Caché grapples with an incredibly contentious topic that incites a deep-seated feeling of uneasiness and sorrow, with the film combining the affairs of a voyeuristic lens to highlight lingering postcolonialism. The film opens with an establishing shot of a wealthy Parisian townhouse, the camera does not move, nor does any significant event happen. That is until the frame jumps, and dialogue interrupts the silence. This segment is of a videotape played on the TV of the couple, Georges (Daniel Auteuil) and Anne (Juliette Binoche). Someone has been filming their daily routine and sinisterly sends it to the confused couple with no apparent rhyme or reason.

Haneke enrols the camera as an ogling character that takes on an omnipresent role of an anonymous figure that continuously torments the family with these unexplained videos, forcing them to recount their every move. This unidentifiable presence behind the camera slowly tortures Georges and Anne by arousing sheer dread and doubt. What makes this film a quintessential entry into Haneke’s oeuvre is the unshakeable secondary narrative that lies beneath the mysterious videotapes: Caché slowly reveals that Georges is not an innocent bystander as these tapes tie into a dark past.

The second act reveals that when Georges was a child, his parents fostered Majid (Maurice Bénichou), an orphan left homeless at the hands of The Algerian War. At the hands of jealousy, Georges conjured a malicious lie that banished this orphan from the house and pushed him out of the comfort of a family home and into a troubled, lonely care system. As the film reconnects Georges with Majid, a sense of repressed guilt is figuratively exhumed via the tapes; they are a corporeal manifestation that what may be hiding in the past still has a tenacious grip in the present.

Caché stands out across all of Haneke’s twelve feature films due to the burgeoning realism that protrudes from the screen and forces the viewer to look at their possibilities of guilt and how sins of the past are ever-present. It is an incredibly compelling film that still bears a hurtful truth eighteen years after its release.

3. Amour (2012)

Every Non-English Language Best Picture Nominee Ranked

Michael Haneke’s Amour is often described as one of the filmmaker’s finest explorations into the fragility of life and the subtle everyday decisions that significantly affect one’s whole existence. Amour is not just heartbreaking in its portrayal of death but also so gut-wrenching and cruel that it trespasses the boundaries of fiction and teeters on the brutal, realistic truths that can come from losing a loved one.

Amour follows Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a retired music teacher struggling through the motions after his beloved wife Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) suffers a stroke. Anne’s incident has left her paralysed on one side of her body, barely able to talk, and a ghost in place of who she once was. Amour holds a tender yet startling mirror up to the viewer that leans towards sympathy whilst also provoking a reaction of fear. Throughout Haneke’s daring, frightening, and dramatic films, Amour is the most alarming.

The touching nature of the film is overtly confronting and raises questions of life, death, and the meaning of it all. And it is within this heartfelt exposition that Amour also unveils some of Haneke’s most visually stunning work.

Haneke has never been one for lavish, extravagant angles. Instead, he opts for the subtle lens, with Amour being no exception; and in this film’s case, a fixed lens has never looked more beautiful. The ‘still’ camera denounces buoyancy to reflect the melancholic atmosphere that encapsulates Georges and Anne’s sedentary lifestyles. Funny Games and Caché utilise an intense gaze to reflect the on-screen chaos. In contrast, Amour employs a certain air of stiffness that coerces complete focus on the sheer emotionality of the script and performances.

Recommended for you: Where to Start with Paul Verhoeven

Michael Haneke is a master in cultivating vile displays of atrocity against a mediocre background, as seen in Funny Games, Cache, and Amour’s predecessor, The White Ribbon (2009). Whilst Haneke showcases life through these confined paradigms, Amour proves that the director does step out of his typical filmmaking style and still has the gumption to explore alternative themes and styles in the mature stages of his career.

Whilst Amour is not entirely estranged from Haneke’s traditional methods, the film highlights a certain emotional sensitivity that Haneke has never displayed so brazenly across all of his work.