A Clockwork Orange In Retrospect – Its Themes, Its Reception and Kubrick’s Directorial Masterclass

This article was written exclusively for The Film Magazine by Lucas Hill-Paul.

Four droogs fill up on Moloko Plus to get them nice and sharpened for a bit of the old ultraviolence. A Clockwork Orange opens with Alex DeLarge smirking defiantly into the eyes of his eager audience in a seamless blend of Kubrickian hallmarks; the arresting symmetry, deliberate camerawork and a camera-conscious protagonist daring us to look away first. The film is about choice, but we’re never given one. Malcolm McDowell’s electric performance is almost always in centre frame, every second compelling his faithful audience to keep their gazes wide open to bear witness to his morbid tale.

It’s impossible to talk about Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange without a brief detailing of its extensive experiences with controversy and backlash. Although the majority of film journos actually praised the film upon its release, contrary to the common assumption that it was widely hated in 1972, Clockwork had its fair share of detractors, and its link to a number of contemporary criminal cases in the UK spurred the age old debate of violence in media having anything to do with violence in reality.

Pauline Kael, one of the most prominent female film academics at the time of the film’s release, reprimanded the film as bad pornography, citing specifically the scenes of sexual assault that she believed were deliberate attempts to titillate. As the film nears its 50-year anniversary and conversations around sexual violence are maturing, it’s difficult to disagree. Yes, Alex’s actions are condemned, but the lens remains squarely on the performers. Much like Taxi Driver or Scarface, one man’s hellish descent into violent disillusion rarely strays from the masculine perspective, and even the women who escape the film unharmed are often merely props to advance Alex’s own biography.

As part of their ongoing season paying tribute to one of England’s finest filmmakers, the BFI is playing host to the film’s first UK cinema screenings in 19 years. I managed to catch The Shining on the big screen in my home town some years ago, but A Clockwork Orange is only the second Kubrick picture I’ve been able to see in cinemas. From the film’s theatrical overture and opening narration, its piping, synthetic musical interludes and complete command of its own pacing, it’s quite clear that the director remains the master of the cinema experience.

Each shocking frame comes to glorious life in this 2K restoration, and after dipping my toes into its big screen release it’s hard to imagine viddying this horrorshow classic a second time without the framing of two blood-red curtains on either side of the old screen. Its delightful retro futurism revels in clinical corridors and long-abandoned neighbourhoods – spaces in which the film’s dark, intellectual protagonist occupies with the presence and hubris of an operatic tragedy’s inevitable victim.

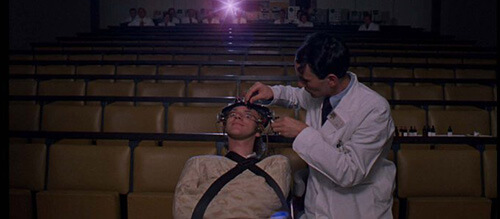

Alex is an egotistical, self-serving maniac but, to me, his free will remains almost entirely intact, despite undergoing extensive psychological torture at the hands of an uncaring, profit-driven government. McDowell’s physical performance in the opening collage of violence and assault is primal and brutish, but always accompanied with a wry smirk, a sharp stare, and, of course, an admiration of the genius composer Ludwig Van. He is beaten and berated, but soon realises that psychological manipulation is not only easier, but more effective.

When Alex collapses in the doorway of one of his former victims’ houses, he recognises the face of Patrick Magee instantly. It’s surely not by happenstance that he then submits the widowed writer to another insidious rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain”. He is subsequently aurally abused with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which drives him to attempted suicide, but he is almost immediately offered a prestigious government position upon his reawakening in hospital.

A Clockwork Orange persistently constructs a dystopian, neglectful state. Alex and his gang of droogs operate outside of the law, but as soon as they come of age their skills of violence are seen as transferable, with Dim and Georgie’s evolution from violent droogs to abusive police officers a sinister premonition of prevalent police brutality that still persists today.

Malcolm McDowell recently sat down with Empire to talk about the film, and while his comments to “get over” the provocative violence are a little predictable, his observation that the film’s climactic moments hinge on a moment of disarming physical comedy feels very astute in light of its themes of unhampered choice, individuality and psychological manipulation. McDowell chomps and slurps helpings of steak and peas being fed to him by the rambling Minister of the Interior, a characteristically rigid and undeniably Tory performance from Anthony Sharp. The Minister is offering everything from apologies to employment (to a literal hooligan) and, when his mouth is empty, Alex pops it open again with an expectant smack of his lips.

After a two hour torrent of torment it’s a relieving comedic release, but this reportedly improvised moment captures so much. A Clockwork Orange is Kubrick’s only film about his adopted country and the particular construction of an apathetic government feels motivated by personal experience. It’s an authoritarian system that cultivates and rewards evil in its enterprise to wipe it out, spoon-feeding a class that despises them whilst plotting their demise. Alex knows this and hates them for it, but what else can he do but make the most of it?

You can support Lucas Hill-Paul at the following links:

Personal Twitter – @lucashpaul

You can find more of his writing at Film Daily News – @FilmDailyNews