Blade Runner 2049: Why is the Female Body the Future’s Prop?

This article was written by Alex Morden Osborne (@mosborne93):

I’ve always loved futuristic and dystopic film and television. Since Doctor Who’s relaunch back in 2005, I’ve avidly consumed space adventures and visions of immense technological advance. Sadly, though, over the years I have been repeatedly met with an unpleasant and fundamental problem at the heart of the mainstream sci-fi genre, which Blade Runner 2049 exemplifies in all manner of ways — blatant, unrelenting sexism.

To begin with a small number of positives, I must say the film’s soundtrack was absolutely brilliant — atmospheric and perfectly paced. Equally, in the most generic terms, it was a beautiful film to look at. This, however, is where my praise ends.

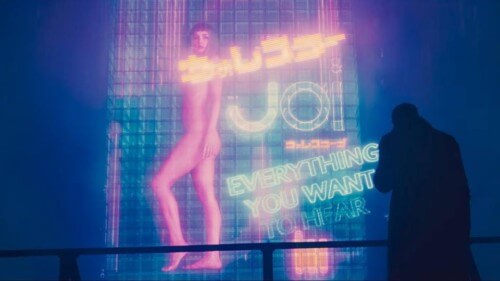

At repeated junctures, the film takes pains to zoom in on distorted, gigantic manifestations of the female form. While wandering in a red-toned desert, Ryan Gosling’s K passes enormous statues of women in stilettos, topless and bent over towards each other in almost grotesque anticipation. On multiple occasions, K sees huge, 3D adverts for Joi, the virtual companions available for purchase in Villeneuve’s version of 2049 LA, which literally transform from second to second dependent on the user’s specific sexual and emotional desires. Typically, no male Joi is advertised — and the female version, predictably well-endowed and visually fulfilling a multitude of stereotypical fanboy fantasies, appears nude, sometimes accompanied with the tagline “everything you want to hear.” All of this grates, of course, though having seen such objectification and voyeuristic pleasure being taken in the female body many times before, I was unsurprised (but no less frustrated) at what I was seeing.

This being said, two scenes in particular did surprise me for their violence and their perversion. The first sees K’s Joi, played by Ana de Armas, responding to his desires by calling the sex worker Mariette, who agrees to have Joi superimpose her image on to Mariette’s body, so that K can sleep with a “real” woman who resembles his perfect, electronic housewife. Mariette is literally used as a vessel. We first encounter K’s Joi in a 1950s getup — she serves him a meal and speaks in soft tones before morphing into a series of different outfits, adhering to her programming by reassuring K that all of his violent and rebellious actions are justified and indicative of his ‘unique’ and ‘special’ character.

During his encounter with Joi/Mariette, K does not acknowledge Mariette at any point, and afterwards, he says nothing to her, instead allowing Joi to promptly dismiss her. As Helen O’Hara pertinently puts it in her own article on the film: “What do filmmakers think of women in general if they choose to focus so overwhelmingly on those who sell sex? […] Prostitutes are over-represented onscreen to almost the same extent that they are stigmatised and marginalised in real life. If we were learning anything nuanced and honest about sex work from these depictions that would be valuable, but generally we’re just watching gorgeous women in revealing costumes draping themselves over men.”

The second particularly troubling scene for me featured Niander Wallace, the cyborg-esque manufacturer of new, apparently obedient replicants, and his favourite replicant Luv, who he refers to as an angel. We are told early on in the film that Luv is incredibly powerful, but that she cannot disobey any order Niander gives her. Questions of fertility are central to the film’s trajectory, with the possibility of a replicant giving birth being hailed as a miracle that has the potential to shatter the traditional role of replicants as slaves. In the scene in question, we see a naked female replicant suspended in a plastic packet released from height. Her gel-covered body falls clumsily to the ground, contorting on impact. She wails in pain, soon to be approached by Niander, who gropes her while aggressively lamenting what is ultimately his failure to develop fertile replicants. With Luv watching on in clear discomfort, he stabs the replicant in the stomach, prompting his ‘angel’ to silently cry, unable to intervene. In many ways, this depressing spectacle highlights wider societal misogyny, which places a woman’s worth in her womb. Indeed, the sadness and poignancy of Rachael’s death in childbirth is brushed over and exploited in order to present Harrison Ford’s Deckard as a sympathetic character, despite the fact that he forced himself on her in the original Blade Runner.

Every prominent female character in the film, by choice or force, ends up sacrificing themselves for a man. Even the brilliant Robin Wright’s Lt. Joshi, arguably the most authoritative woman in the film, is presented as mildly infatuated with K. Her feelings eventually lead her to cover up his recklessness, which results in her violent murder at the hands of Luv. Any agency she has is torn from her, as her death is presented as necessary collateral damage for K’s personal advancement. The violence women endure and the damage it does to their bodies takes visual and narrative precedence over their thoughts and actions.

What frustrates me the most about all this is that futuristic films are, by their very nature, driven by potentiality — the possibility, in vast new worlds or reimagined old ones, to challenge and disrupt the norms and order of how we live now. Yet time and time again, such films pass over this opportunity by performing and reiterating the sexualisation and typecasting of women and girls that is equally prevalent off-screen. Even recent sci-fi films with female leads, such as Arrival and Gravity, deny the fundamental power and intelligence of the women at their hearts by reiterating their statuses as mothers above all else — presented as weakened and blinded by overstated maternal instincts and emotions.

With disturbing reports emerging about Harvey Weinstein exposing the institutional sexism at work in the film industry, it’s all the more necessary to challenge the predictable female narratives it so often produces. And so I say, to filmmakers from all genres — the female body is not your prop.

Show your support for this article by following Alex on Twitter at: @mosborne93

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]

Alex cosplaying white knight and puritan at the same time. How the left has joined the evangelical right. Scary.

Thank you, you encapsulated everything perfectly that I despised about that movie/universe. Great article, I hope you write more :)