A Retrospective Look at The Passion of the Christ and Its Artistic/Cultural Merits

“He was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities, through His wounds we are healed”

-Isiah 53; 700 BC.

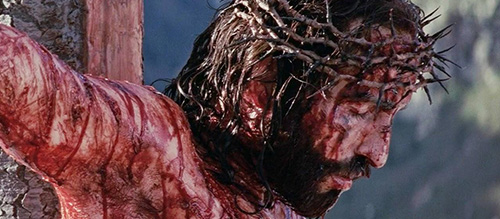

Starting with a verse from Isiah’s prophecy of “The Suffering Servant”, Mel Gibson made his intentions very clear that his dramatization of Jesus Christ’s last 12 hours on Earth would tear through the “PG” depiction of Christ’s passion which has infiltrated cinema since its beginning. Thus came about the production of one of the most controversial and hyped-up movies of this century. The bloody violence and gore had itself a hefty 18-rating whacked onto the film, with “The Passion” as a whole becoming subject of much heavy criticism. I specifically remember people’s barely contained awe, shock and excitement in the whispering campaigns in anticipation for the movie, with rumours of the star’s (Caviezel’s) near death-experiences during production. Almost immediately after its release, stories began to circulate of “Road to Emmaus” type conversions in both audiences and cast-members, and of criminals turning themselves into the police. I remember my parents going on a trip to the cinema to see it as part of our local parish outing, and as an 11-year-old at the time, I just remember feeling like the whole thing was so bizarre – it was also the only 18-rated film my parents allowed me to watch at the time.

Over a decade later, Mel Gibson announced that a sequel was in the works – The Resurrection of the Christ – and I cringed, for you see, to summarise in one word how I feel about the former movie it would be: uncomfortable. This may seem quite odd to any regular readers who will know that I adore and have praised several “bible” movies including The Prince of Egypt and The Miracle Maker, but upon re-watching Passion, I have found it to be a two-pronged issue with elements of the actual filmmaking and the movie’s overall impact on the world leaving me slightly perturbed.

Author’s note: Before we go any further, I understand that one of Mel Gibson’s intentions would have been to make the audience uncomfortable, but let’s just see where this piece takes us.

To go back to my introductory point, The Passion of the Christ was Mel Gibson’s directorial attempt to produce an authentic realisation of Jesus of Nazareth’s final day on Earth, according to the Gospels; from the Aramaic and Latin language that would have been used by the ordinary people of the time to the brutality and bloodlust the Roman Empire has been famous for throughout history. But for what ends were these meticulous means taken for? Was this film made for Catholics and Christians to serve in the reinvigoration and realisation of their faith? Or, was it to bring the story of Christ further afield? To quote the Gospels – to “Go and make disciples of all nations…”? I will be discussing these intentions more deeply later, but I would first like to focus on whether the movie’s execution succeeds in inspiring faith in, or deepening the faith of its audience.

Speaking from my own experience as a Catholic, The Passion Story is incredibly important: Jesus’ sacrifice represents God’s love for us, and the lengths he will take for us, bearing the cost of the evil of humanity throughout all of time to spare us the cost of our own actions (so that we can then spend eternity with him). The central story of Christian Doctrine becomes even more personal to me as an individual, recognising that Jesus being a man would go through the same experience as all other humans – the emotional, mental and physical pain of torture and mocking, despairing loneliness as your closest friends betray and abandon you, and of course the ultimate human experience – the fear of death. Knowing God went through these same anxieties and trials on my behalf has always made my observance of Good Friday and Holy Thursday very emotional. So, to me, dramatizations of Christ’s life such as The Miracle Maker and Jesus of Nazareth, have physically deepened my faith, as to see the tangible pain and suffering Jesus went through is a far more moving, transforming experience than hearing it read out from scripture. So, does Mel Gibson’s attempt to depict an accurate account of the sadistically cruel nature of Jesus’ death serve to provide an experience in faith for me? My answer would have to be no.

When I re-watched The Passion of the Christ for this article, I repeatedly found myself disinterested and bored. There were moments of genuine shock and sorrow but, in all honesty, they were far and few between. I felt every minute of the two-hour run-time as the bungled execution left me emotionally unattached from the unfolding plot. Much of the fault can be laid at the writing and directing’s door as several poor elements contributed to my boredom, the most significant of which is the gratuitous violence. The first time I saw the film I was genuinely rattled by what I saw – the movie succeeded in causing me to reflect upon Christ’s suffering during his Passion. However, I was only 11 at the time and this was R-rated violence, something we’ve already established I wasn’t used to. As time has passed, I have watched a great deal of adult content in movies over the years and have been exposed to more violence in cinema. Like all media-addled youths I have become desensitised, but this is no excuse to any filmmakers as I can think of several times the use of violence has impressed me in the movies: I laughed till I cried at Timothy Dalton’s impaling by a miniature church steeple in Hot Fuzz, I reeled in my seat at Kurt Russell’s brutal punch to “Daisy Domergue’s” face in the The Hateful 8, and I remember the almost nauseating shock at the infamous tongue scene from Oldboy.

On a basic level, the amount of violence is impressive but it failed to make an emotional connection, and that is such a cinematic faux pas – violence without reason – especially for a supposedly “holy” film. For one thing, it hindered the actors’ performances – and this is almost an injustice in the context that Caviezel (in the titular role) worked his arse off in this movie from having to emote through a dead language, to nearly dying of hypothermia and asphyxiation. But as soon as Jesus gets knocked around, Caviezel then had to try to act through incredibly heavy make-up and it is evident how much more difficult it became to project an emotional performance through these unwelcome additions. On a shallow note, a more resonating performance may have been achieved if the film was English speaking. Usually I love foreign language films, but in this case the Aramaic and the Latin tongue serve to be an additional degree of removal from the story. Furthermore, the violence fails to bring home the poignancy of the story as the Passion of the Christ has a very similar filming style to other violent blockbusters of the time: the frequently used slow-motion brought Gladiator and even The Matrix to mind, which simply gives the movie a copycat quality – as time passes The Passion of the Christ only has potential to become more unremarkable against its more superior contemporaries of that era. This is a very frustrating conclusion to make as there are a few choice moments of direction which did make my heart ache, the most notable of which was the actual crucifixion scene as Caviezel screams whilst nailed to the cross (his best performance in the movie) as Morgenstern’s Mary squeezes dirt in her hands as her heart is pierced by the sight of her son dying before her. The power of this scene does, however, actually highlight the over-arching issues of the film’s narrative and unfortunately reminds us of what we potentially could have been given.

Morgenstern’s heart-breaking performance as Mary watching Jesus be crucified is one of the many small interactions with Christ by the supporting roles and extras which succeed in achieving the movie’s seemingly intended goal. These infinitesimally small moments as guilt, pity and compassion flit across the faces of the likes of Barrabas, St Veronica and Simon of Cyrene are the parts of the movie which are the most spiritually transforming. It is these small intimate seconds in which audience becomes a part of the movie and of scripture – for to quote Isiah’s Suffering Servant:

“He has no stately form or majesty that we should look upon Him, Nor appearance that we should be attracted to Him. He was despised and forsaken of men,”.

In these brief flashes I realised part of my relationship with Jesus: conflicted, wanting to tear my eyes away from his wretched state but compelled to look on, knowing he drags himself to this pitiful existence for my sake. In writing this, I’m almost angry that these moments are drowned out by the rest of this cumbersome movie as its focus lies largely elsewhere. These brief scenes stand as testament that Mel Gibson bit off more than he could chew in deciding to make a 2-hour movie based on the Passion.

Ultimately what makes The Passion story so powerful is our ability to put ourselves within it, especially in the Christian context of Christ dying for our sins, but this can only be achieved if we find the situation relatable, and this is the cause of audiences turning off during The Passion of Christ. The tale is over-stretched and the supporting characters are neglected. Even Christ himself is in some dire need of exposition, and this is directly caused by only focusing on his story from the Garden of Gethsemane to his death. I believe Mel Gibson knew this too as flashback scenes litter the narrative, almost as if in hope of the audience actually feeling something. Many of these flashback scenes may be stirring but they are a poor alternative to fully complex characterisations. In comparison, The Miracle Maker, an animation based on the story of Jesus aimed at children and families, illustrates an insatiably charismatic and enormously compassionate Christ – it succeeds in making the audience fall in love with him despite being only 90 minutes long. This is because it shows his life and mission within its entirety and you see the incredible effect he has on people’s lives: Simon Peter feels too ashamed to associate with him after Jesus’ miraculous catch, knowing he is an unworthy, sinful man; Mary Magdalene’s unwavering love and adoration for him as Jesus saved her when he could have dismissed her as an unworthy, irredeemable woman like everyone else did. You also understand why he gains such a frenzied following and why those in power plot against him (especially as the film actually bothers to address the political issues of Jesus’ society) – so when the account of the Passion finally comes (which is all done within 15 minutes) you are led into a powerful experience, convinced of how frightened Jesus was of this fate and of his bravery to face it anyway, and all with hardly any blood shown. It deepens the faith. The Passion of the Christ may have also had this power if showed the larger story of Christ, most importantly his ability to reach into the most jaded of people’s hearts. For a film bursting with Catholic influence, it just seems really odd to feature the Resurrection as some sort of after-thought: Christianity wouldn’t even be a thing if we didn’t believe he rose from the dead because, if we didn’t, Jesus of Nazareth would have just been a dude from the past with some ideas which got him killed, the end.

You know, it could make a person think that this movie is supposed to be a guilt trip or something…

In terms of lack of characterisation, the film has issues that exceed that of a lack of empathy from which the audience can draw, and this is where most of the film’s controversy stems from. To be quite literal, if I closed my eyes and tried to conjure up images from The Passion of the Christ, what I tend to see first are the jeering, laughing faces of the Roman Soldiers who tortured and executed Jesus. This alone represents much of what is wrong with The Passion of the Christ as the “villains” of the piece are the prime example of the poor writing and direction of the movie. I appreciate that bloodlust is an uncomfortable aspect of humanity that has followed us through history and an issue we still need to keep in check today – if public executions were a thing today, tonnes of people would still go. However, it is totally overplayed, especially in the case of the Roman soldiers whose actions and reactions seem very unnatural and as a consequence bring you crashing back into reality and out of the movie. I actually re-watched the film with my Dad, and several times throughout the movie he rolled his eyes, sighed and actually pointed out the overacting of those playing these characters, commenting on how unrealistic the performances were. It also brings to mind the troubling idea that this film was intended to be an attempted conversion by guilt trip, by focusing on the torture Jesus suffered.

The issue here comes when the two-dimensional characterisation of the supporting roles strays from lazy and bad writing, to downright offensive when considering characters such as the members of the Sanhedrin. The Sanhedrin were, basically, the religious leaders of the ancient Jewish/Hebrew religion of the time (in which the Temple in Jerusalem was of central importance), and according to the Gospels, they were the group that plotted against Jesus to have him executed by the Romans. It is their depiction in The Passion of Christ which caused outcries and accusations of anti-Semitism from Jewish and Gentile audiences alike. With repeated viewings I do agree with these claims: the direction and writing produces performances which are almost caricature-like. Sbragia as Caiphas, the Chief Priest, is almost laughable as his performance consists of put-upon sneers and jeers; I’m surprised he didn’t rub his hands together in anticipation and glee whilst Jesus was tried by Pontius Pilate. Without wanting to open a theological can of worms, I have been reflecting on whether The Passion Story in all its adaptions and accounts can be free of anti-Semitism, but that’s a question I don’t really have the faculties and research to answer. Furthermore people have argued against the claims of Anti-Semitism with regards to the depiction of the Sanhedrin, saying that the Jewish religion practiced in the time of Jesus was very different to modern-day Judaism and that the Sanhedrin are not openly identified as being Jewish, but I believe that’s a very obtuse argument to make for throughout the history of Christianity, the Passion story has been used to discriminate against Jewish people in the claim that they are “Christ-Killers” with disastrous impacts that would be impossible to encompass in one article.

Films are not made by accident, what we see is the result of deliberate decisions – Mel Gibson knew what he was doing, and there are examples of dramatisation of The Passion in which sensitivity has clearly been exercised. Such a dramatisation is the TV miniseries Jesus of Nazareth, in which Jewish producer Sir Lew Grade and Catholic director Franco Zeffirelli were anxious to produce something “acceptable to all denominations” including “non-believers”. Zeffirelli even consulted experts from different faiths including people from the Vatican, the Leo Baeck Rabbinical College of London, and The Koranic School at Meknes. Consideration of peoples of all creeds is as such evident – a moment that comes to mind is the beginning of the final episode in which the Sanhedrin gather to discuss what to do about Jesus. Thus unfolds intriguing exchanges between a council of elders representing a rich and complex faith and heritage, men who have lived through politically and socially chaotic times with brutal mass executions of their brethren by the Romans fresh in their minds. Within this 10 minute scene, you see the multi-pronged issues Jesus’ mission represents: anxieties that his teachings will incite a Zionist riot which will incur the wrath of their Roman Occupiers, whispered confessions of believing that he may be the Messiah, along with fear that he undermines their power. In comparison The Passion of the Christ fails to give a reason as to why Jesus has been arrested. The only reason that is presented is because the Sanhedrin hate him, and even then their hatred goes largely unjustified. So why the difference? Well, Zeffirelli made the conscious effort to not demonise Jewish people in the depiction of the Crucifixion, Gibson on the other hand… well, comments he made a few years after the film were made speak volumes enough don’t they? According to an article in The Guardian (Stephen Bates), Zeffirelli criticised Gibson in 2004 for perpetuating harmful Jewish stereotypes, depicting them as “sinisterly attracted to the most unrestrained violence”

As I mentioned before, I have contemplated whether the Passion story can ever be presented completely free of anti-Semitic connotations, but have concluded that in the very least Jesus of Nazareth shows what can be achieved when mindfulness is applied to the production. If a production from nearly thirty years prior can show respect and sensitivity to faiths other than Christianity, is it really acceptable for The Passion of the Christ to have been so deficient in this area? I think not. Especially in the context of the time this film came out. In all honesty, I don’t think the mere idea of this film would have been dreamt of if the events of 9/11 had not come about – an aspect of the production and the film’s reception I feel is vitally important. Films like the Raimi’s Spiderman trilogy, Superman Returns, the Bourne trilogy, The Dark Knight, even Bruce Almighty, represent the anxiety of the American identity under threat and their attempt to reassert it in the world from around the same time, and it’s a completely understandable sentiment, but an aspect which became included in the validation of the national identity was Christianity, something I feel did have potentially negative connotations.

The likes of Donald Trump in the States and Theresa May in the UK use Christianity as a means of justifying their politics. They use it, as many historical leaders have done, to justify that these countries are of a moral superiority compared to others, and it’s frustrating to see this as a Catholic, because the way they use it encourages a fear of otherness. “Otherness” meaning anything that doesn’t fit in the basic model of western conservative Christian society. Travellers from targeted Islamic countries were banned from America whilst individuals who came to America as children face deportation as adults, and it’s all done under the lie and façade of preserving the “Christian Culture”, and this is the same kind of morality religious bullshit that was used to justify the Bush administration regarding action in Iraq and Afghanistan, which the whole world is still reeling from today. Now obviously, I can’t blame these complex political issues on a movie, but The Passion of the Christ is symptomatic of the troubles of that era. It plays into the idea of Christianity being under threat (which in places like the UK and the US it simply is not; something I feel is grossly insensitive to the fact of the real persecution some Christians face in other places around the globe) and attempts to reassert Christian identity upon the world. The Passion of the Christ had so much potential – it came at a time where the world was in desperate need of healing. Based on the basic preaching of the Gospels, seeds of friendship and brotherhood could have been sown between warring and differing communities in the spirit of loving everyone, even those who would do you harm. A reaffirming film for Christians and Catholics to learn again the importance of forgiveness and mercy. Instead, what came out was an almost aggressive conversion piece – “LOOK AT WHAT THEY DID TO HIM”… almost. During that time of deep hurt, it should have known better; again, I know that this movie shouldn’t bear the responsibility, but it is part of an attitude I believe has led to the resurgence of the fear of the other, allowing for space for hate groups to flower again.

So here we are at the end of this article, and to be honest I think I’ve scared myself a bit. To look at The Passion of the Christ as simply a film worthy of critique, my critique would be that it isn’t very good – it’s overly long, the direction was clumsy and led to poor performances by the actors, and with each consecutive watch I find it harder to remain engaged, often finding myself wishing I was watching something else. Unlike many of the films and series I have seen made on Jesus’ life, it has had the least emotional resonance with me and had the most meagre impact on my faith. On these counts alone I find it difficult to validate this movie’s success and popularity. On a more serious note, I simply do not wish to accept a movie which uses Jesus Christ’s message and story to create rifts between people it identifies as different to one another. We face difficult times ahead, and to get through this we need to learn to accept each other regardless of who we are – I wish to be blessed with the overwhelming desire to help and love everyone who is in need, and in this cause we shouldn’t tolerate those who try to build walls between us. All in all, there are much better films and TV series about Jesus Christ out there. I do hope that Mel Gibson, in his wilderness years, has learned something new through which to atone for the sins of The Passion with his intended sequel Resurrection.

Great blog Katie very well-written!

The Passion of Christ In Light of the Holy Shroud of Turin was called the greatest relic in Christendom by Pope John Paul II. In fact, the Shroud is the most studied scientific object in the entire world.

Thanks,

Rev. Francis

This is the most ridiculous “review” I have ever read. You clearly have no idea what you are talking about apart from your more than obvious purpose of serving a specific political and social agenda. Also, it might be interest you to know that there is a phrase known as “in my opinion.”

Isn’t “in my opinion” implied in any given analysis of art?