Dennis Hopper’s Last Movies: ‘Homeless’, ‘Pashmy Dream’

In 1971, American actor and director Dennis Hopper released his second directorial film The Last Movie. After the era-defining Easy Rider (1969) had become a critical and commercial success, there was much anticipation for Hopper’s new film and the cultural and societal messaging the director and actor would sneak in. Afterall, Easy Rider had seemingly defined the counterculture of the 1960s. This excitement didn’t just come from the audience’s perspective, but the film studio bosses who saw Hopper and his New Hollywood cohort as a revolutionary force (and financially viable) in filmmaking and American culture as a whole. Thus, Hopper and a whole group of young and inexperienced directors were given funds and carte blanche over their productions.

Alas, The Last Movie was almost a prophetic title. Instead of a straight forward narrative that bopped along on a striking soundtrack of rock and roll standards like Easy Rider had two years prior, The Last Movie was a disjointed, non-linear, visual and audio assault. The film was a condemnation of the exploitative nature and practices of Hollywood moviemaking and U.S imperialism, interference, and colonialism. Immensely disliked by the executives and financial backers at Universal Studios who had handed Hopper a one million dollar budget and complete creative control, the film was only given a two week opening stint in a select number of theaters and drive-ins. Although it was awarded the prestigious Critics Prize at the 32nd Venice International Film Festival, The Last Movie was buried and Hopper’s directorial career was considered over. Hopper retreated to his New Mexico compound, drank a great deal, took a lot of drugs, and entered into a sulk that would last for the next fifteen years.

As he was ostracized from mainstream film, Hopper spent the 1970s working as an actor in a wide-range of American independents and foreign films. The best of these could be considered Mad Dog Morgan (1976), Tracks (1977), and The American Friend (1977). The worst might be eurotrash obscurities such as Last In, First Out (1978), and The Sky Is Falling (1979).

However, The Last Movie would not turn out to be Hopper’s last directorial film. In a stroke of good luck, good timing, and an inexperienced director who bailed on the project, Hopper took control of the Canadian film Out of the Blue (1980). What was originally intended as a family-friendly television movie, Hopper repositioned as an urgent-two fingered salute from the punk rock generation to the hippies. The film didn’t have a wide release and due to its subject matter of familial destruction, substance abuse, and incest, was handed the same fate as The Last Movie; buried and left to be forgotten.

Thankfully, both these films, from the lost period of Hopper’s exile, have faced renewed interest over the past few years with restorations, reissues on DVD and Blu-ray, screenings at international film festivals, and extensive documentaries and articles re-examining Hopper’s iconoclast films.

From 1986 onwards, a clean, sober, and healthy Hopper reaffirmed his position within mainstream Hollywood and independent films alike. Three successive performances in Blue Velvet, River’s Edge, and Hooisers (all released in ‘86) introduced him to a new generation of film audiences (the hippies’ kids) and reminded those that were present during the 1960s what an extensive force of nature Hopper was. He was welcomed back with open arms.

It was inevitable that Hopper’s re-entry into Hollywood would offer him opportunities to direct films again. They came thick and fast, starting with Colors (1988) and proceeding in fairly quick succession with Catchfire (1990), The Hot Spot (1990), and his final feature film Chasers (1994). This quartet of films demonstrated Hopper’s quality, finesse, and expertise as a steady film director. They might lack the fire, passion, iconoclast tendency, political commentary, and capturing of the zeitgeist seen in the trifecta of Easy Rider, The Last Movie, and Out of the Blue, but, as demonstrated by Colors, Hopper knew how to sell the film to a younger, hipper, and more in-tune audience with the inclusion of a solid soundtrack of hip-hop standards. Colors should perhaps be regarded as a bridge between the works of independence seen in Easy Rider, The Last Movie, and Out of the Blue and the works as a Hollywood director for hire on Catchfire, The Hot Spot and Chasers.

The bawdy sex-comedy Chasers unfairly ended Hopper’s tenure as a feature film director. The film is technically Hopper’s very last movie. Yet it wouldn’t be the final time Hopper took up residence behind the camera. There are two directorial credits that follow Chasers. The digitally shot short film Homeless (2000) and the Gwyneth Paltrow-starring advertisement Pashmy Dream (2008). While both these short films don’t offer the bravado of previous works, they are worth investigating as a way to understand where Hopper might have gone if allowed to continue on his directorial path.

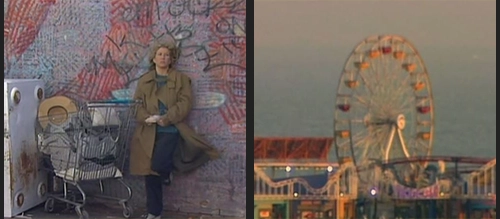

In Homeless, a young unhoused woman spends her days pushing a shopping cart of belongings around a seaside California town. In flashback we see that the woman was once an exotic dancer. Hopper doesn’t layer the film in any romanticism, and instead uses grainy and flat digital film to produce an up-close and voyeuristic documentary of this unnamed woman’s life. She glides through the city unacknowledged by passers-by. In the flashbacks of her days as a dancer, we see her dance semi-naked to music. Her face is made up and her blonde hair is gleaming and clean. In the present day, she looks more or less the same, but her body is hidden under tatty and baggy clothing. Her face is covered in grime and her hair is tattered and dirty. She is the same person, but she is invisible in her current guise. Her time as a dancer would have no doubt drawn a crowd who would have considered her attractive, but wouldn’t look at her now.

Homeless was produced as part of an online film festival that was to have been hosted and judged by Hopper and Quentin Tarantino sometime in 2000. The film was intended as an example of the type of entries they were looking for. With the cancellation of the festival, the film has instead entered (alongside his abstract paintings, sculptures, and photography) the lexicon of Hopper’s artistic works and was shown on a loop as part of his many worldwide exhibitions.

Homeless had been an idea of Hopper’s for a while. He had told American Film magazine way back 1988 that he was keen to direct a “a little, De Sica-like film about the homeless in Los Angeles.” Hopper’s referral to Italian director Vittorio De Sica hinted at an interest in telling stories from the perspective of the poor and the working class of American society. De Sica had taken this perspective in many of his films, most notably in his Oscar-winning Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1968).

Interest in the marginalized certainly extends to Hopper’s first four directorial films. He profiled the counterculture, the hippies and other societal outcasts in Easy Rider. Through the lens of Hollywood movies, he shone a light on the exploitation of indigenous populations in The Last Movie. In Out of the Blue he sought to explore the hardships of a working class family ripped apart by drugs, alcohol, and abuse in a small community torn apart by tragedy. And, while coming from the perspective of LAPD police officers, he gave exposure to the trend of gang membership, and the emergence of hip-hop music in Colors. These first four films show Hopper to be a canny social critic. Homeless comes from that same stance, but due to some obvious constraints the film isn’t given the space it needs to work as a serious commentary on homelessness and the policies that impact unhoused people. It is a nine minute film, with very little funding, and a lack of narrative. There is a notable lack of music or score which was something of a celebrated trait of Hopper’s previous films. His devotion to the use of popular music in Easy Rider, Out of the Blue, and Colors was intended as a signpost to the eras in which they were made, but also flagged to the audience the politics of the times.

While Hopper’s first four films are interested in the protagonist’s relationship to society and the wider culture, his last three films are more interested in relationships that occur between men and women. The social commentary is dropped from Catchfire, The Hot Spot, and Chasers in favor of sexual politics, streamy affairs, and rotten betrayals. While these films certainly have merit, they are not as fondly remembered, nor have they faced the same critical reassessment as Hopper’s first four films. They are certainly flashier, more expensive, and have a cast of familiar faces in lead and supporting roles. Hopper’s two last movies also exhibit this divide. Homeless comes from the avant-garde, cinéma vérité leanings, and improvisational, on-the-fly nature of Hopper’s earlier works. His final directorial piece Pashmy Dream shares far more with the lavish productions of his last three feature length films.

Hopper’s Pashmy Dream is a modern retelling of the story of Cinderella. In this case the glass slipper that is returned by a charming prince is a Tod’s pashmy bag. Cinderella is Gwyneth Paltrow playing a version of herself, and the prince is a handsome Italian journalist.

Paltrow wanders through an Italian market place and meets with the journalist for an interview about an undisclosed film that has just finished production. She is in Italy for an extravagant wrap party. As the interview begins, the table is suddenly swarmed by paparazzi. Overwhelmed, Paltrow flees the scene. The journalist sees that Paltrow has left behind her plush Tod’s pashmy bag and pursues her across the city with repeated cries of “Gwyneth, your bag!”

Unlike Homeless, which focuses on just one subject with very limited interaction with the surroundings, Pashmy Dream contains multiple performers, elaborate sets, and even music. While the focus is on Paltrow and the journalist, they both move through a vastly populated city and have numerous interactions. Eventually the journalist tracks Paltrow down to a lavish party attended by a multitude of well-groomed guests and circus performers. The journalist reunites Paltrow with her beloved bag and the two share a dance. A nice touch of consistency.

Hopper once stated that “All my films end in fire,” and indeed most of them do. Easy Rider’s last shot is a burning motorcycle, the last shot in Out of the Blue shows the cab of a rig in flames, The Last Movie shows the protagonist, Kansas, repeatedly getting shot and “going down in flames.” Surprisingly, Pashmy Dream ends with a fire breather from the wrap party blowing a flame across the screen. Hopper’s literal last movie ends in flames.

Homeless and Pashmy Dream may only exist as curiosities or footnotes in Hopper’s career as a film director, but they can be considered essential to Hopper’s creative output. They could also be considered as missed opportunities. A longer running time and an assortment of characters and challenges overcome by them could have made Homeless an intriguing document of the unhoused and ignored population of the cities we inhabit. A longer film could have been a damning indictment of the political unwillingness to engage with a societal issue that has only got more apparent and more rampant over the past decades.

Pashmy Dream on the other hand wraps up its premise satisfactorily within the time it’s given. There really isn’t much more meat on the bone to pull off. It borders on smugness which would possibly spill further into cringeworthy and irksome fluff if it went on any longer. Hopper’s aesthetic as a film director would not have gelled with a Hallmark-style romantic movie, which is the film’s only apparent outcome. The tired premise of a handsome man reacquainting a lost item to a beautiful woman has been repeated endlessly for centuries and doesn’t hold much intrigue. The film is, afterall, a prolonged advertisement for an expensive bag. Nonetheless, it’s an extravagant production that at least shows Hopper was able to juggle the numerous challenges that a big budget film would have brought.

What has always been intriguing about Dennis Hopper is the vast expanse of media his life covered. He was a prolific actor, a dedicated artist and photographer, a patron of the arts and an avid collector of artists ranging from Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat to Julian Schnabel. He appeared in big-budget Hollywood movies and self-funded indie films. He was also a recognisable celebrity with notorious stories of drug-related exploits that fueled the tabloids for decades. He even hosted ‘Saturday Night Live’. But his work as a director is sparse. Seven films spread over a four decade period is limited no matter how impactful one or two of them was to a generation of film audiences. There should have been more entries in Hopper’s arsenal of directorial films, and Hopper himself believed this and expressed regret that the opportunities fell through.

Dennis Hopper’s feature directorial work is just a facet in our understanding of what made him such a unique talent within almost all the creative fields he explored. Be it a cameo role in a Hollywood movie, a supporting role in an indie film, a series of abstract paintings, a collection of polaroids of gang graffiti, a TV spot selling life insurance or a sensible car, or a television advert for a posh bag starring a Hollywood actress. He surfed high art and low culture effortlessly. It is worth investigating even his smallest contribution to popular culture or art to further that understanding.

Written by Stephen Lee Naish

Stephen Lee Naish (he/him) is a writer and visual artist. His work explores film, politics, and popular culture. He often examines political undercurrents present in films and their potential for social commentary and critique. He explores a wide range of topics, including the impacts of COVID on theaters, the class war of the 1% upon the rest, and the climate crisis. He has written essays for various journals and periodicals, including Candid Magazine, The Quietus, Albumism, Aquarium Drunkard, Film International, and Dirty Movies. He is also the author of several books including “Create or Die: Essays on the Artistry of Dennis Hopper” (AUP), “Deconstructing Dirty Dancing” (Zero Books), and “Riffs and Meaning” (Headpress). His latest book is “Screen Captures: Film in the Age of Emergency” (Newstar Books). He lives in Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Linktree: Ste L Naish

Twitter: @RiffsandMeaning